Bruteforcing LUKS Volumes Explained

Some weeks back, we were forced to reboot one of our server machines because it stopped responding. When the machine came back up, we were greeted with a password prompt to decrypt the partition. No problem, since we always used a password combination (ok, permutation) that consisted of a few words, something along the lines of “john”, “doe”, “1954”, and the server’s serial number. Except that it didn’t work, and we forgot the permutation rules AND whether we used “john” “doe” or “jack” “daniels”.

All the search results for bruteforcing LUKS are largely the same – “use cryptsetup luksOpen --test-passphrase”. In my case, the physical server is in the server room, and I don’t want to stand in front of the rack trying to figure all this out. My question is, can I do this offline on another machine? None of those blog entries were helpful in this regard.

The LUKS Header

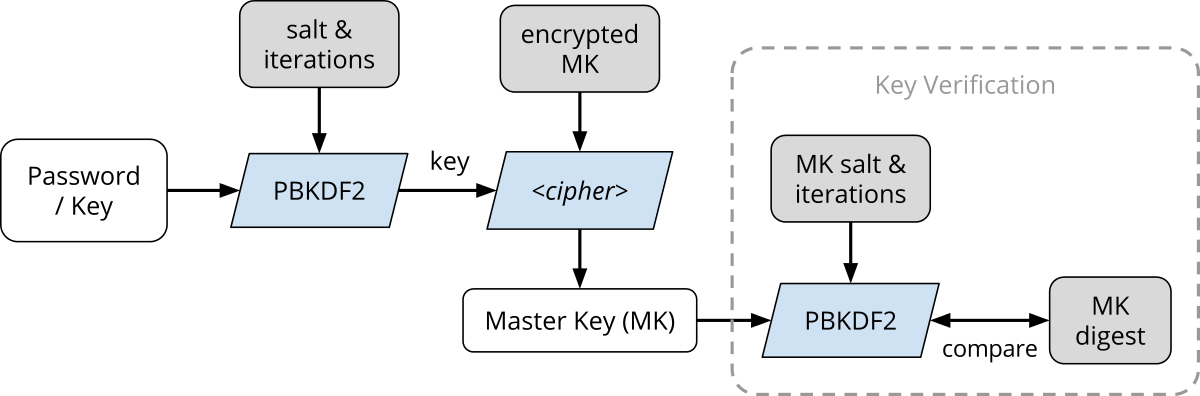

To answer this question, I took a look at the LUKS header. This header is what provides multiple “key slots”, allowing you to specify up to 8 passwords or key files that can decrypt the volume. cryptsetup is the standard userspace tool (and library) to manipulate and mount LUKS volumes. Since LUKS was designed based on TKS1, the TKS1 document referenced by the cryptsetup project was very helpful. After consulting the documentation & code, I came up with the following diagram that describes the LUKS key verification process:

Basically, rectangular blocks represent pieces of data and parallelograms represent processes, specifically crypto operations. Gray data blocks are stored in the LUKS header, whereas clear data blocks are not.

- The user-provided password goes through the standard Password-Based Key Derivation Function 2 (PBKDF2), with the parameters specified in the LUKS header.

- This forms a key, which is then used to decrypt (using the specified block cipher and mode) the encrypted master key (MK) that is stored in anti-forensics (AF) stripes. The AF stripes cause the key to be stored across a large amount of disk space, such that the erasure of a single stripe renders the key unrecoverable.

- Once the master key (MK) is decrypted, it can be used to decrypt the data stored in the volume.

- LUKS provides a means for verifying the master key by having stored the MK digest. This digest is also computed using PBKDF2, but using a different set of parameters. By comparing the computed MK digest against the one stored in the header, the correctness of the MK (and hence the user password) can be verified.

As you can see, the LUKS header (plus key slot area) alone is sufficient for the recovery of passwords or key files. Given an input password, its correctness can be verified by going through PBKDF2, block cipher decryption, followed by another PBKDF2. Thus to prevent bruteforcing, the number of PBKDF2 iterations are chosen such that they take a sufficiently long time (1000 ms) for one verification on that particular machine. The various parameters stored in the header can be viewed using cryptsetup luksDump.

The LUKS header can be extracted using cryptsetup:

cryptsetup luksHeaderBackup \

--header-backup-file /path/to/save-headers \

/dev/encrypted-partition

Once the header has been extracted, the conventional luksOpen technique so commonly described can be used on this backup file.

Bruteforcing the Password

Initially, I looked at John the Ripper, a popular password bruteforcing tool. I found that it does have LUKS support in the bleeding-jumbo branch. Apparently you use the luks2john utility to preprocess the LUKS partition/header, then use john to actually bruteforce the processed file. However it didn’t work. Also, I couldn’t find a way to make it use password combination like the ones I described earlier.

I fell back to using just a Python script that calls cryptsetup, because the bruteforce was definitely not going to take long and that was not worth optimizing or constructing an elaborate program:

#!/usr/bin/python

from itertools import permutations

import subprocess

import sys

words = ['jack', 'daniels', 'john', 'doe', '1952', 'c5295bfeed0']

luks_file = sys.argv[1]

for combo in permutations(words, 4):

passwd = ''.join(combo)

print 'Trying %s...' % repr(passwd)

r = subprocess.call('echo %s | cryptsetup luksOpen --test-passphrase %s' % (passwd, luks_file),

shell=True, stdout=None, stderr=None)

if r == 0:

print 'Password is %s\n' % repr(passwd)

breakTake note that the cryptsetup bundled with CentOS allocates a device first, for the verification of passphrase as well as mounting:

Enter passphrase for /home/darell/luks-header.bin:

# Trying to open key slot 0 [ACTIVE_LAST]

# Reading key slot 0 area.

# Allocating a free loop device.

Cannot use a loopback device, running as non-root user.

Device /home/darell/luks-header.bin doesn't exist or access denied.For this reason, it makes the bruteforcing process slightly slower and it also requires root privileges. You will therefore want to use a fairly recent cryptsetup, at least version 1.6.6, which processes the LUKS key slots in userspace instead (commit a3c0f6), removing the need for root privileges when verifying passphrases. Here is the speed comparison for 19 tries:

- cryptsetup 1.6.3 – 14.744 s

- cryptsetup 1.7.0 – 14.098 s

- speed up: 0.646 s

Avoiding the device allocation and setup saves more than half a second, which isn’t much but it does add up over several iterations. There are probably more efficient ways to bruteforce LUKS, such as using multiple threads instead of just one. That’s exactly what bruteforce-luks (GitHub) does, and by directly invoking the cryptsetup API, the process fork costs are eliminated. I did not use this because it performs a “dumb” bruteforce, and it doesn’t support custom passwords rules like the combinations I mentioned.

Good News Everyone!

Fortunately, we managed to recover the password for the server and disaster has been averted.

Going forward, a truly random password will be generated for LUKS encryption to avoid someone bruteforcing the password as we have done. To achieve a high bus factor and to ensure “business continuity”, this password will be printed out and placed in a sealed envelope for safe-keeping by trusted persons. To reduce the chances of someone having to reach for the envelope, we can deploy the mechanism I developed for my home server earlier this year that automatically unlocks the LUKS volume.